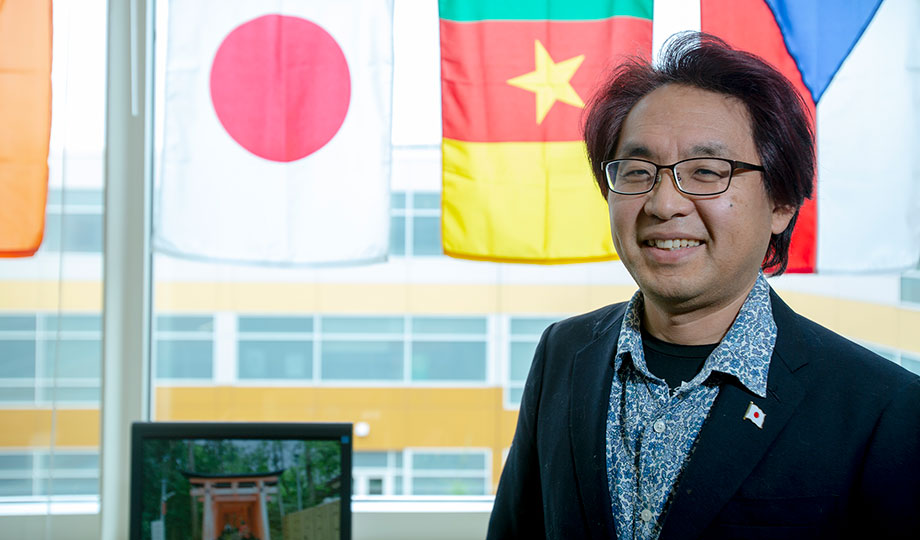

Program: Languages

His educational path was clear: Shingo Satsutani was going to be an engineer.

He completed his studies, knowing he could get a well-paying job. But Satsutani was drawn to Western philosophy, an interest that would take him in a direction he never imagined.

Now the Japan native has made a home for himself at College of DuPage, teaching Japanese to eager students and introducing a wide range of students to the beauty, history and culture of his country.

"I knew I'd become a teacher because of the good teachers I encountered during elementary school, high school and college. Although early on, I didn't know I wanted to be a teacher," Satsutani said, with a laugh.

While his friends from school went on to work for multimillion-dollar companies, Satsutani got involved in social student activism, including the anti-Apartheid movement. The experience not only allowed him to grow as an individual, but also helped him build a strong sense of right.

"I said, 'Well I can't just go to work for multinational companies who are abusing people.' That was it," he said. That's when I went to philosophy."

Satsutani's approach to teaching Japanese is relaxed. While some may have more difficulty than others in grasping the language, he compares language skills with musical talent.

Regardless of any inherent skills, Satsutani's students are encouraged to enjoy the moment, taking in as much information as they can to create a more global view of the world. It's a large part of the reason Satsutani leads classes to Japan through COD's Field Studies program.

"Japan is small, you know," he said. "Imagine half the U.S. population living in 30 percent of California."

But with the constantly evolving communications world, the globe seems to be getting smaller. People can speak to each other from other sides of the world in real time and companies now spread across several continents. Educating people in other cultures, therefore, is becoming more and more important, Satsutani said.

This was evident when a massive earthquake and tsunami struck his homeland in 2011. Less than 72 hours after the catastrophe, Satsutani wrote in his blog that Japan and its people will rise again. Such hope in the face of hardship is common in this culture, and it's tested time and time again.

"In some respects, Japan is a good friend to natural disasters," said Satsutani, explaining that the mountainous island nation is situated on fault lines, home to an active volcano, and vulnerable to major typhoons. People there have learned to be cautious – and accepting of things in life far beyond their control.

"We do have a national characteristic, we call it resignation to the life. That means don't go against the flow of the water. You just flow in and you float," he said. "Something happened, OK, you accept what happened, and just don't go against that. You start from there and little by little things get better."

In the days and weeks that followed the March 11 disaster, the world saw another national characteristic at work as Japanese people maintained an amazing sense of decorum. The darker side of human nature so prevalent in other recent catastrophes, like Hurricane Katrina and the Haiti earthquake, seemed absent in Japan. Satsutani said bad things like looting happened in Japan too, but on a much smaller scale.

"Here in the U.S., no matter how people are looking at you, you're not really worried about it. I do what I have to do, and I'm right. But over in Japan one thing that is important is how you are looked at, how you are watched by the people. From that context, if you do behave wrong, from the standard, then you're standing out and the people look at you as negative. Even though in that bad situation of a natural disaster, that comes first in your mind, and you don't want to look bad," said Satsutani, who began teaching at COD in 1994, a year before another major earthquake struck the western side of Japan, where his mother still lives, taking 6,000 lives in its wake.

Today, he says, it's beautiful there again, a road to recovery more than 15 years in the making. Communities in western Japan have welcomed evacuees from the eastern part of the island, helping them to heal and rebuild their lives.

Satsutani enjoys introducing students to a new language and a new way of life. It also gives them an opportunity to learn a language more complicated than the Latin languages taught in most American high schools, he said.

"Japanese is not out of the Latin languages, so you have to maneuver three different writing systems," Satsutani explained. "Japanese has 100 characters, plus some imported from Chinese, but it's easier to learn Japanese if students have studied Spanish or German because of the phonetics."

The country's history also plays a role, not only in Satsutani's language classes but in his study abroad courses as well. Most students go into the trip with a pre-conceived notion of the experience, but those assumptions fall far short of reality, he said.

"Students really learn there's history there,' he said of Japan. "When I say old, they think a couple hundred years, because America is so young. But I mean old!"

Learn more about the Languages program at College of DuPage